In the wake of earthquakes and pandemics, Ōtautahi has experienced a profound metamorphosis, both physically and culturally. A resurgence in inner city development is undoubtedly a positive aspect, however, it has brought with it a notable increase in noise-related complaints that loom a possibility of venue closures and a call for a change toward an outdated infrastructure.

At the intersection of gentrification and noise regulations lies a critical juncture for the music culture that has long been at the heart of the identity of Ōtautahi. As our city undergoes this seismic transformation, it is vital to acknowledge these challenges are not insurmountable and provide us as a community an opportunity to adapt and contribute to the sustainability of the cultural landscape of Ōtautahi.

The coexistence of nightlife and residential living has become a pivotal concern, driven by the outdated infrastructure of post-quake noise regulations that entwine the city. A notable divide arises as urban development breathes new life in Ōtautahi while potentially silencing the core of its vibrancy.

The urgency to find a suitable balance has been met with a proactive - rather than reactive - approach from a handful of venue owners and organisations which has led the City Council to contemplate a reevaluation of its distinct plan.

From the early 20th century, music venues have provided a platform for a broad scope of our creative inhabitants while being instrumental for the growth of many communities. Our city’s musical heritage has taken many shapes and forms that resonate with the unique cadence that continues to shape the many scenes we have today.

Noise complaints are certainly no thing of the past. However, there were fewer inner-city residents and a lack of council presence. Music venues could instead let the culture thrive without the threat of having their licence challenged.

Under post-quake governance, Ōtautahi found itself rising from the rubble, a chance to revitalise the city. Amidst the difficulties, there were signs of resilience and adaptability, with DIY parties and alternative venues hosting live music.

They scribed the opportunity to diversify and expand their offerings, showing the city’s determination to rebuild and revitalise its music scene in the face of adversity.

Ōtautahi had never seen loss like we did in 2011, facing copious unprecedented challenges due to the major earthquakes that devastated the city, leading to the closure of the CBD and most music venues. The impact of this upheaval was felt deeply by the local music scene, resulting in the destruction of iconic inner city music venues and tertiary institutions that were cultivating the next generation of creatives.

While regulations are essential for fostering balance in an urban environment, the current situation often poses an ultimatum of forced compromise onto venue owners as the wave of gentrification washes over commercial zones. A lack of consideration has put immense pressure on them to comply with the outdated noise regulations while upholding the economic and cultural viability of their establishments in an environment that no longer suits them.

2023’s Christchurch City Council’s Central City Noise survey sought to hear from individuals and businesses in Ōtautahi.

3,399 individuals and businesses responded to the survey between September and October. The survey found that nearly 40% of central city residents were bothered by various types of noise. Yet overall, survey respondents were supportive of Ōtautahi-Christchurch’s night time economy, understanding that “living in the central city comes hand-in-hand with increased noise levels.”

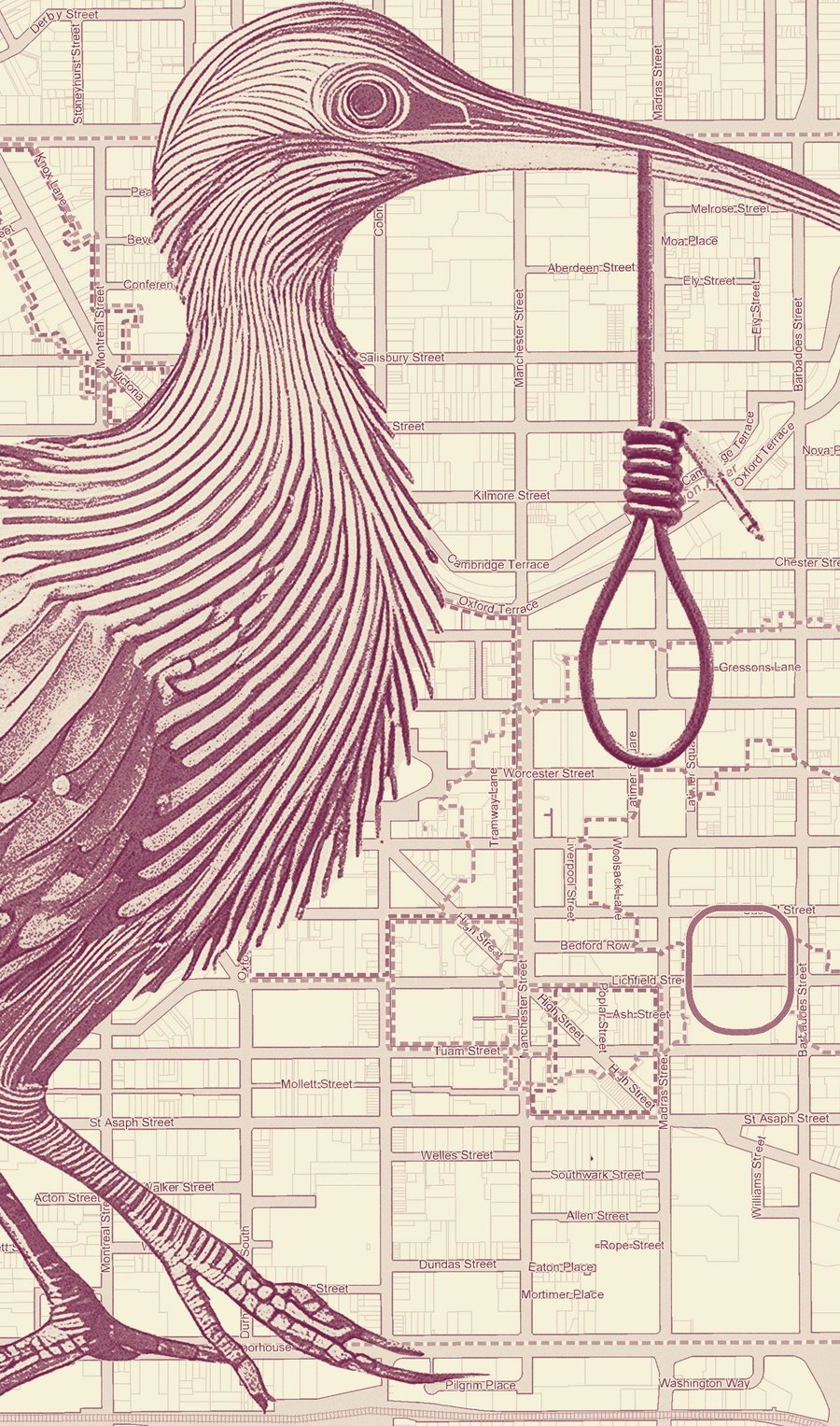

Christchurch’s prospective target of having 20,000 residents in the central city by 2028 places urgency on solidifying a sustainable noise management system between venue owners and CBD inhabitants. Considering the fact that the CBD population currently stands at 8,830, a significant increase of the CBD population is anticipated for the city.

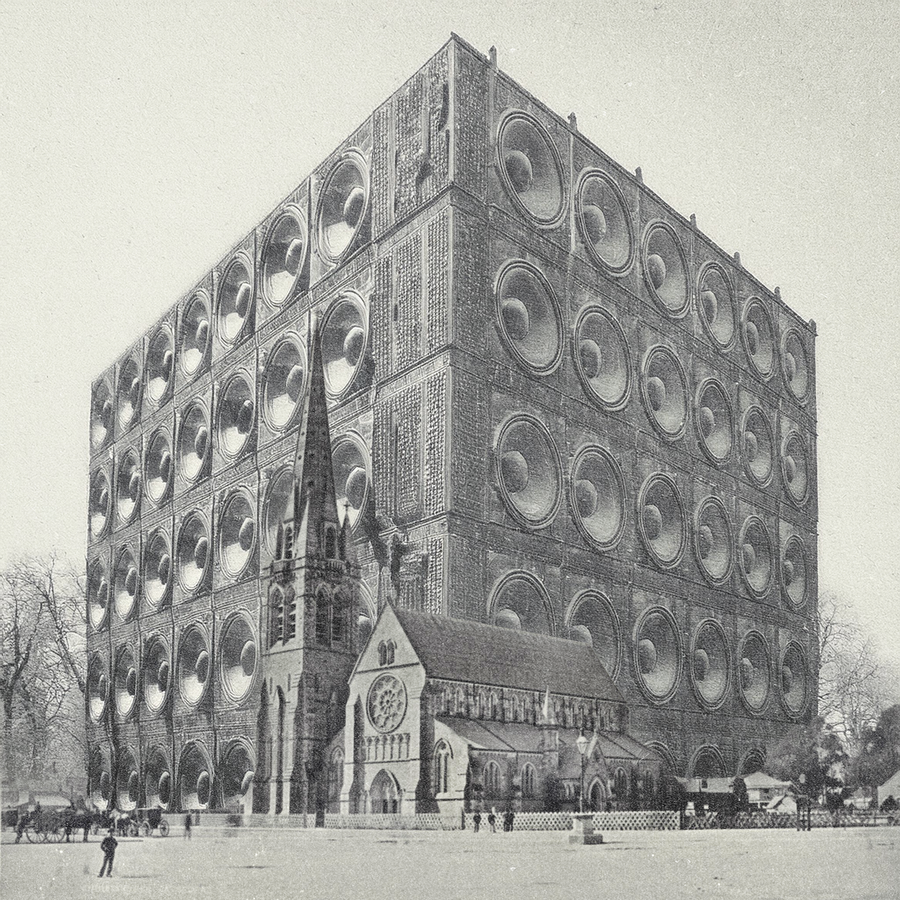

The current noise limit before 10pm is 60dB, which is generally equates to an unobtrusive volume of an unobtrusive volume of a typical conversation, snoring, toilet flushing, vacuum or the noise of a car idling. It is virtually impossible to operate a venue at 60dB, it strips the atmosphere of any sort of energy and dynamic that encompasses an immersive experience into our city’s culture.

After 10pm, there is no specific decibel level listed as a “noise limit.” Rather any noise that is considered as “excessive” or “unreasonably interfering with the peace and comfort of others” is not permitted. The City Council provides noise control guidelines on their website for specific details on acceptable noise limits.

Licence renewal applications are reviewed collectively by the District Licensing Committee, Noise Control, Police, and the health board and which are the main threats for venue owners. If a recurring pattern of noise complaints emerges, it automatically triggers opposition to the licence renewal. This sparks the debate on whether noise control, and licensing, should function separately from one another.

Noise emission zoning is divided into three precincts, each carrying its own set of varying noise standards that align to the intended operation of each space. The first precinct is Category 1, for higher noise level entertainment and hospitality precincts.

Second is Category 2, for lower noise level entertainment and hospitality precincts. And then Category 3 for all Central City areas other than Category 1 and 2 entertainment and hospitality precincts.

Currently, the liveliest districts in town are not appropriately zoned for higher noise levels and the most permissive precinct is the least utilised, a two-block area surrounding the long stagnant remains of the Sol Square development.

Noise sensitivity in mixed use areas may lead to conflicts, an instance known as ‘reverse sensitivity,’ where new inhabitants complain about existing noise sources. Amendments in the city plan are crucial for addressing noise issues. Drawing inspiration from the innovative Agent of Change principle employed by the Australian Victorian state government, these amendments could effectively safeguard music venues from the encroachment of new residential developments. This principle places greater responsibility on entities like residential developers, requiring them to incorporate noise attenuation measures within 50 metres of existing live music venues, thus ensuring the sustainable coexistence of music venues and residents.

The earthquake and the subsequent COVID pandemic took a toll on artists and venues, leaving them disenfranchised and severely disrupted the hospitality and music industry’s ability to operate, with venues in financial hardship.

Venues facilitate the cultural undercurrent that binds communities that value artistic expression, creating jobs in both the music and hospitality industries that make huge contributions in cultivating our city’s vibrancy, economy, and enthusiasm toward supporting a better future.

Without our venues, the heart of our local music culture, we risk being devoid of the culture that has come to define us. Gigs would remain mere aspirations, our talented artists would lack the stages to flourish and inspire, generations would lose their cherished gathering places and our city would grapple with a cultural void, leaving it an uninspiring place to call home. It is why we must assert ourselves as a city against the noise regulation odds to maintain the vibrancy and richness of Ōtautahi.